There are a few names that, even to non-scientists, are representative of sea changes in the history of scientific discovery: Galileo. Newton. Darwin. Tesla. Hawking.

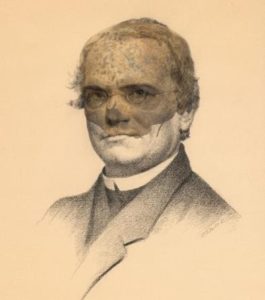

Among those names is Gregor Johann Mendel, the humble, unassuming Augustinian monk from Brno, in modern-day Czech Republic, whose work with plants helped establish the foundational principles of inheritance, adhered to by geneticists to this day.

Finding the “Father of Genetics”

Gregor Mendel

Often referred to as the “father of genetics,” almost every student who takes even an introductory course in biology encounters Mendel’s work, most famously his experiments involving cross-pollination of pea plants. Thanks to careful observation and meticulous notetaking, Mendel observed inheritance patterns in several traits of the plant such as the flower color, pea texture etc., eventually discovering the concepts of dominant and recessive genes, as well as developing a method to predict hereditary outcomes in organisms that would extend well beyond the plants in his garden.

As his 200th birthday approached in July of 2022, scientists in his hometown decided to commemorate their most famous resident by locating his remains and sequencing his genome. Not only would it be a poetic way to honor the Father of Genetics, it would allow the world to understand Mendel in a deeper way, and introduce his legacy to a new generation.

Where Was Mendel Buried?

There was just one problem: no one knew exactly where Mendel was buried.

Pictured: Šárka Pospíšilová

Image courtesy of Šárka Pospíšilová

The idea gained traction among city representatives in Brno and Masaryk University. The university’s Vice Rector, Šárka Pospíšilová, head of the Department of Medical Genetics and Genomics at the Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital Brno, as well as Head of the Center of Molecular Medicine at the Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC MU), was in a unique position to form and organize the interdisciplinary team needed to locate analyze his remains and, ultimately, perform a thorough analysis on his genetic material. While her main research focus is on genetic analyses of leukemic patients, being a geneticist by training, Pospíšilová was enthusiastic about a project with such broad appeal: “I want to promote the popularization of science, and the search for the genome of the father of genetics is an exceptional opportunity to draw everyone’s attention to science in a way they can understand,” she said.

Pictured: Excavating the gravesite – the tomb.

Image courtesy of Photo Archive, Masaryk University

While they were certain he was laid to rest in the Augustinian tomb in the central Brno cemetery, his gravesite had never been officially identified. The cemetery had been established only two months before his death in 1884, and the Augustinian tomb was established a year later, making it “questionable whether his remains were buried in the same place as other Augustinian brothers,” Pospíšilová admitted.

In order to locate and identify his body, Pospíšilová had to assemble a cross-functional team. The group ultimately included anthropologists and paleontologists from Masaryk University, geneticists from CEITEC MU, and archaeologists from both Masaryk University and ARCHAIA Brno, a local archeological nonprofit. Once assembled, they began the lengthy process of getting permission to access the gravesite. They had to approach not only Brno city officials, but also the Augustinian monks, who themselves had to seek permission from officials in both Prague and Rome. Luckily, everyone involved shared their enthusiasm for the project: “They were very open to such kind of research, and all of them agreed and were also very enthusiastic about the research of the tomb,” recalled Pospíšilová.

Pictured: Excavating the gravesite.

Image courtesy of Masaryk University

By June of 2021 they were ready to begin. The team focused on one particular gravesite that they knew contained the remains of four monks, one of whom, they suspected, was Gregor Mendel. As with many scientific endeavors, the process of excavation was not without surprises.

Perhaps the biggest was the discovery of a fifth, unexpected set of remains that were later identified with a high probability to be those of Abbot Napp, the monk who had accepted Mendel to the order in 1843.

The second surprise was in the final coffin that was uncovered. The bottom of the coffin was lined with newspaper, and still legible was the date: October 1883, three months before Mendel’s death. “It was the first proof that we discovered that this was the coffin with Mendel’s remains,” recounts Pospíšilová. “Still, we needed to get some additional proof.”

Pictured: The team examining the remains.

Image courtesy of LBMA UEB, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University

Pictured: The hair sample being collected from Populäre Astronomie, one of Mendel’s books.

Image courtesy of Dana Fialová

The monks gave the researchers access to some of Mendel’s personal belongings, including his gardening tools, glasses, and several books, in the hopes of being able to recover some of his DNA. There, between the pages of one of his astronomy books, they found a strand of hair. DNA was extracted from the hair, as well as from the teeth found in the coffin, using the Applied Biosystems™ PrepFiler™ Forensic DNA Extraction Kit, amplified using the Applied Biosystems™ ProFlex™ PCR System, followed by Sanger sequencing of the mitochondrial hypervariable region to screen for the presence of mitochondrial DNA. The mitogenomes were then analyzed, and those from the hair were compared to those found in the teeth – they were a 100% match.

For further confirmation, the team analyzed the skull found in the coffin, performing CT and X-ray analysis and comparing it to photographs of Mendel. They matched as well. After more than 130 years, Gregor Mendel had been found.

Archaeology, Anthropology, and Genetics Working Together

Pictured: The skull matched against a photo of Gregor Mendel.

Image courtesy of Eva Drozdová

“We succeeded in getting archaeological proof, with the location of the coffin and newspapers along the bottom, then anthropological proof, with the age of the remains and X-ray analysis of the skull, then genetic proof from the full sequence match of the mitochondrial DNA from his hair and teeth” Pospíšilová said, emphasizing the serendipity of every piece of evidence falling neatly into place, a rarity in science of this nature.

Pictured: Gregor Mendel’s remains.

Image courtesy of Masaryk University

The sequencing of Mendel’s genome took place over the next several months; due to the degraded nature of the archaic genetic material, specialized bioinformatic algorithms had to be used to piece together his DNA sequence. The full genome was fully sequenced in January of 2022.

Further Insight to Mendel’s Life Through Genetic Data

Beyond the symbolism of the project, the team was also interested in learning more about the health conditions Mendel may have had that led to his death at the relatively young age of 61. While it was already known that he suffered from kidney problems, the team was curious to investigate whether he had any genetic variants linked with cardiovascular disease, due to reports that he suffered from hypertension. Their hypothesis proved correct: within his genome they discovered pathogenic variants in several genes associated with multiple cardiac disorders including cardiac arrythmia and Long QT Syndrome.

These genetic data, combined with autopsy results noting a hypertrophic heart, throw the currently-accepted theory that he died from kidney disease into question. “We believe that it’s highly likely he died from cardiac infarction” Pospíšilová said. She points to evidence that he was working and signing documents until the day before his death, indicating a sudden death typical of cardiovascular disease.

Pictured: Augustinian monks return the remains to the gravesite.

Image courtesy of Šárka Pospíšilová

The team concluded their work on all five sets of the remains in November of 2021, and the bodies were returned to their final resting place in a ceremony attended by Augustinians from all over the world. “It was very nice that, thanks to Mendel, the Augustinians met with the researchers, and everyone involved in the project, in the abbey after the funeral. They had the possibility to discuss and remember one of the most important members of the Order,” recalls Pospíšilová.

While Mendel has been returned to his tomb, his legacy is far from over. Pospíšilová is especially proud of how this project brought together so many different types of scientists: the archaeologists who helped excavate the gravesite, the anthropologists who analyzed the remains, the geneticists who sequenced the genome, the bioinformaticians who processed the genetic data, and the chemists and renovators who helped to protect the clothing and other artifacts found in the tomb. Pospíšilová hopes that the collaboration established between these teams is something that will continue into the future. “It’s helping to boost scientific teams,” she said, “and this novel idea came thanks to Mendel. So he’s still helping science, even after his death.”

—