Connect to Science celebrates Women’s History Month and Black History Month by remembering life science pioneers

Throughout history, the contributions of women in STEM have often been overlooked.

However, these 10 remarkable women scientists left an indelible mark on the world. Their groundbreaking achievements not only advanced scientific knowledge but paved the way for aspiring scientists to follow in their footsteps.

Join us as we delve into the remarkable accomplishments of these trailblazing women.

1. Sarah Elizabeth Stewart, Pioneer of Viral Oncology

1905-1976

Sarah Elizabeth Stewart (Public Domain, NIH History Office)

Born in Tecalitlán, Jalisco, Sarah Elizabeth Stewart migrated to the United States with her family when she was just 6 years old to escape the Mexican Revolution.

Stewart earned her doctorate in microbiology in 1939 and began working as a professor of bacteriology at Georgetown University School of Medicine – unofficially attending medical courses until the school finally began allowing women to enroll in 1947. Stewart was the first woman to earn an MD from the university.

Through her studies, she joined the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and sought funding to explore a link between viruses and cancer. The NIH denied her initial requests because the idea of cancer-causing viruses was not yet accepted by the scientific community, and because the program did not believe Stewart was qualified to pursue cancer research as a woman and virologist.

Undeterred, Stewart went on to demonstrate the existence of cancer-causing polyomaviruses with her NIH colleague Bernice Eddy, definitively proving a link between infection and tumor development. Her work, twice-nominated for the Nobel Prize, was key to the development of the HPV vaccination to prevent cervical cancer.

2. Susan La Flesche Picotte, First Native American Physician

1865-1915

Susan La Flesche Picotte was born in 1865 on the Omaha Reservation, shortly after the tribe had been forced to relinquish much of their land to the United States government for reallocation within Nebraska.

La Flesche Picotte was inspired to pursue medicine from a young age, after witnessing the death of an Omaha woman because a local white doctor refused care. Determined to provide quality healthcare to her own community, she became the first Native American woman to earn a medical degree – from the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, one of the very few medical schools willing to accept women or scholars of color at that time.

After graduating as valedictorian, she spent her career providing care to the Omaha Reservation community, championing tribal public health issues, operating a private practice with her husband to treat patients of all ethnicities, and fulfilling her life dream of opening a hospital.

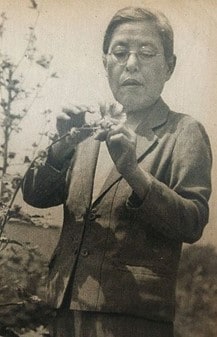

3. Kono Yasui, Plant Biologist and Japan’s First Female Ph.D.

1880-1971

Kono Yasui was the oldest of nine children, born at the height of Japan’s Meiji era in which women were more able to receive an education than their predecessors, but still faced strongly gendered social expectations limiting their career options.

Yasui developed an early interest in botany, studying fern morphology and becoming the first Japanese woman to publish in an academic journal. Eventually, she applied to the Japanese Ministry of Education to study plant cell biology abroad. The Ministry permitted her study under the conditions that Yasui list “home economics research” alongside “scientific research” on her application, and that she agree not to marry – dedicating her life to scientific inquiry instead.

In the United States, she pursued her doctorate at Harvard University studying changes in plant tissue during carbonization and coal formation. Her thesis revealed that geological forces, rather than microbial activity, transform plant matter into sediment.

As the first Japanese woman to earn a PhD, she forged a successful career in plant genetics – founding the journal Cytologia, authoring 99 publications, and leading a 1945 survey of plants affected by nuclear fallout after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She also helped to establish a national university for women in Tokyo, Ochanomizu University.

4. Jewel Plummer Cobb, STEM Equity Leader who Characterized Melanoma

1924-2017

Growing up in segregated Chicago, Jewel Plummer Cobb defied an unjust education system by becoming just one of several brilliant scientists in her family. Her father was a Cornell-trained physician and his father, a freed slave, graduated from Howard University with a degree in pharmacy in 1898.

Cobb had planned to become a physical education teacher like her mother until her sophomore year in high school, when she peered through a microscope for the first time. This experience kickstarted an extraordinary career in cell biology and cancer research.

Her research characterized the relationship between melanin production and melanoma, along with the effects of hormones, UV light, and chemotherapy on cell division. In collaboration with her contemporary Jane Cooke Wright, she discovered that methotrexate was effective in the treatment of certain skin, lung and pediatric blood cancers.

As a strong advocate for Black scholarship, Cobb also balanced her research with other leadership pursuits including serving as the first Black dean at Connecticut College and the first Black woman appointed to the National Science Board. She used these roles to establish innovative resources for underrepresented students pursuing STEM careers.

5. Ruth Hubbard, Biochemist and Social Activist

1924-2016

Ruth Hubbard was born to a pair of Jewish physicians in Vienna, Austria in 1924, fourteen years before Nazi Germany annexed the country. As a teenager, she fled with her family to the United States and settled into a new life in Boston, Mass.

There, her interest in the sciences blossomed and Hubbard attended Radcliffe College – a sister institution to Harvard, where women were not yet allowed to enroll – to study biochemistry. Her research in the field contributed to our essential understanding of vision and photoreceptor mechanisms.

By the late 1960’s, however, Hubbard’s keen interest in benchwork waned as she saw science enter the warfront of Vietnam as destructive weaponry and harsh chemical defoliants. At the same time, she began challenging what she viewed as the inequitable power structures of academic STEM environments that favored white men. Though a struggle, she became the first woman at Harvard to gain tenure in biology.

Her later work shifted towards exploring the social intersections of science, philosophy, and racism, and she became a deeply influential figure in modern bioethics and feminism. She championed equity in science until her death in 2016.

6. Jane Cooke Wright, “Mother of Chemotherapy” and Health Equity Advocate

1919-2013

Like her contemporary Jewel Plummer Cobb, Jane Cooke Wright came from a family well-versed in science and social justice. Her father Louis T. Wright was one of the first Black graduates of Harvard Medical School, longtime chairman of the NAACP, and founder of the Cancer Research Center at Harlem Hospital where he was New York City’s first Black surgeon in a non-segregated setting.

Following closely in his footsteps, Jane earned her medical degree, joined the oncology staff at Harlem Hospital, and acted as a passionate advocate for addressing racial medical disparities and integrating the healthcare system.

At Harlem Hospital, the father-daughter duo set out to advance the nascent science of chemotherapy – still highly experimental and far from standard of care in the field – and make it accessible to patients of all backgrounds. Louis worked in the lab identifying anti-cancer chemical drug candidates, and Jane performed patient trials. In 1951, their seminal work established the first evidence of methotrexate efficacy in treating breast cancer. When Louis died a year later, Jane became director of the Cancer Research Center. Her work in the oncology field continued for decades and was integral in bringing chemotherapy into the mainstream.

Aside from her pioneering work in chemotherapy, Wright also developed the technique of using human tissue culture in lieu of lab mice to test the effects of potential drugs on cancer cells.

7. Gerty Theresa Cori, First Female Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine

1896-1957

Gerty Theresa Cori and her husband in the lab (Smithsonian)

Austro-Hungarian-American biochemist Gerty Theresa Cori became the first woman to earn the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1947 – alongside her husband and an Argentinian colleague – for discovering the lactic acid or Cori cycle of carbohydrate metabolism. Gerty’s father suffered from diabetes, and the Coris wanted to facilitate a cure by understanding the mechanisms controlling blood glucose and insulin in the body.

As a Jewish woman in the early twentieth century, Gerty faced intense career discrimination in both Europe and America. Though she performed her Nobel-winning work as an equal research collaborator with her husband Carl at Washington University, she only earned one-tenth the salary.

The Coris continued to work as a team for the next decade, and their expertise drew collaborations with seven future Nobel Laureates. Unfortunately, Gerty learned that she had the fatal illness myelosclerosis the same year that she received her Nobel, and she died in 1957.

8. Gertrude Elion, Architect of Targeted Drug Design

1918-1999

Gertrude Elion (Public Domain, NIH)

Gertrude Elion received the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her innovative (and now standard) method of rational drug design, which replaced hugely inefficient, trial-and-error drug screenings with a pointed strategy of using prior chemical understanding of the biological target to inform optimal therapeutic design.

Elion grew up in the Bronx as the daughter of Jewish Eastern European immigrants. Though she was interested in science from a young age, few chemistry opportunities were available to women at that time. Her family had gone bankrupt in the stock market crash of 1929, but Elion’s strong grades earned her a full scholarship to college. By only 19, she had earned her chemistry degree.

Completing her training as a Jewish woman posed a financial struggle. She accepted an unpaid lab assistantship and enrolled in a chemistry graduate program as the only female student. She completed her Master’s thesis research at night and worked as a secretary and New York public school substitute teacher during the day to support herself.

Using rational drug design, she developed the first immunosuppressive drug – used to fight organ transplant rejection – and treatments for gout, malaria, meningitis, sepsis, herpes, leukemia, and more. Her development of acyclovir also ushered in an era of antivirals that culminated in AZT, the first AIDS drug. Elion’s discoveries opened the floodgates for new, accelerated paths in medical research that continue into today.

9. Roseli Ocampo-Friedmann, Extremophile Expert

1937-2005

Roseli Ocampo-Friedmann was a Filipino-American botanist and microbiologist who detailed life on the in extreme environments.

During her travels with her biologist husband Imre Friedmann, she discovered more than 1000 microorganisms living in extreme environmental conditions – including in an Antarctic desert previously thought to be lifeless. These extremophiles included cyanobacteria and other lifeforms capable of withstanding intense heat, cold, salt, and pressures.

Her findings piqued the interest of NASA in their pursuit of life on Mars, though even on Earth they have expanded our understanding of the limits of habitability.

10. Flossie Wong-Staal, Visionary Virologist who Characterized HIV-AIDS Link

1946-2020

Flossie Wong-Staal (Public Domain, NIH)

Born Wong Yee Ching in Guangzhou, China, Wong-Staal became “Flossie” when the American nuns at her Catholic primary school suggested that she change her name to something more westernized. Her father chose Flossie after the name of a recent typhoon that had struck Shanghai.

Wong-Staal left Hong Kong at 18 to attend the University of California, Los Angeles. From there, she landed at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the 1970’s to begin researching retroviruses – an obscure category of viruses at that time. This work enabled Wong-Staal and her mentor Robert Gallo to recognize the signature of a retrovirus at work when a mysterious disease that we now know as AIDS began emerging.

Wong-Staal was the first to clone the HIV virus and “dissect” its components – notably, a protein that became the target of AIDS drug AZT and another that led to the development of protease inhibitors.

Though Wong-Staal passed away in 2020 of complications from pneumonia, her groundbreaking work with one epidemic in HIV-AIDS built a strong foundation for another in today’s SARS-CoV-2 research.

» Read about 9 more women in STEM history

Want to read more stories like this? Subscribe to Connect to Science, your portal for life science news.

References

American Chemical Society. “Carl and Gerty Cori and Carbohydrate Metabolism.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/carbohydratemetabolism.html.

Association for Women in Science. “Roseli Ocampo-Friedmann, PhD,” May 5, 2022. https://awis.org/historical-women/roseli-ocampo-friedman/.

Cancer History Project. “Remembering Jane Cooke Wright, a Black Woman, Who Was among Seven Founders of ASCO.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://cancerhistoryproject.com/people/remembering-jane-cooke-wright-a-black-woman-who-was-among-seven-founders-of-asco.

“Celebrating Black History Month – Jane Cooke Wright | Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://mbb.yale.edu/news/celebrating-black-history-month-jane-cooke-wright.

“Changing the Face of Medicine | Jane Cooke Wright.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_336.html/.

Corbett, Sara. “Ruth Hubbard Challenged the Male Model of Science.” The New York Times, December 21, 2016, sec. Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/12/21/magazine/the-lives-they-lived-ruth-hubbard.html, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/12/21/magazine/the-lives-they-lived-ruth-hubbard.html.

Flam, Faye. “Flossie Wong-Staal, Who Unlocked Mystery of H. I. V. , Dies at 73.” The New York Times, July 17, 2020, sec. Science. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/17/science/flossie-wong-staal-who-unlocked-mystery-of-hiv-dies-at-73.html.

gazettejohnbaglione. “Ruth Hubbard Wald, 92.” Harvard Gazette, March 8, 2017. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2017/03/ruth-hubbard-wald-92/.

Hively, Will. “Looking for Life in All the Wrong Places.” Discover Magazine. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/looking-for-life-in-all-the-wrong-places.

“In Memoriam: Flossie Wong-Staal, Ph.D. | Center for Cancer Research.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://ccr.cancer.gov/news/article/in-memoriam-flossie-wong-staal-phd.

McNeill, Leila. “How a Pioneering Botanist Broke Down Japan’s Gender Barriers.” Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-pioneering-botanist-broke-down-japans-gender-barriers-180967595/.

National Library of Medicine. “Changing the Face of Medicine | Susan La Flesche Picotte.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_253.html.

Nelson, Sarah. “Biologist Flossie Wong-Staal Remembered for Pioneering HIV Research and Treatments.” Daily Bruin. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://dailybruin.com/2020/08/06/biologist-flossie-wong-staal-remembered-for-pioneering-hiv-research-and-treatments/.

Nobel Foundation. “The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1947.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1947/cori-gt/biographical/.

Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum. “Stewart, Sarah.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://history.nih.gov/display/history/Stewart%2C+Sarah.

School of Medicine. “Biography of Sarah Elizabeth Stewart, MD, PhD.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://som.georgetown.edu/stewartsocietybio/.

Talladega College. “Dr. Jewel Plummer Cobb, Black Woman Scientist and Trailblazing Researcher | Featured Alumni .” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.talladega.edu/featured-alumni/dr-jewel-plummer-cobb-black-woman-scientist-and-trailblazing-researcher/.

The Jackson Laboratory. “Women in Science: Jewel Plummer Cobb (1924-2017).” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.jax.org/news-and-insights/jax-blog/2018/may/women-in-science-jewel-plummer-cobb.

The Nobel Foundation. “The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1988.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1988/elion/biographical/.

“The Nobel Prize | Women Who Changed Science | Gertrude Elion.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/womenwhochangedscience/stories/gertrude-elion.

Vaughan, Carson. “The Incredible Legacy of Susan La Flesche, the First Native American to Earn a Medical Degree.” Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/incredible-legacy-susan-la-flesche-first-native-american-earn-medical-degree-180962332/.

Leave a Reply